I often think it’s a real pity that so many students seem to actively dislike learning about plants. Why is this? Is it because plants don’t seem to ‘do’ anything interesting? I used some of the information described here in a test question this year – the results were a salutory reminder to spend more time working with students on how to read and interpret data sets.

One of the Biology Standards year 13 students [currently] study is called ‘Describe animal behaviour & plant responses’. Now, if ‘behaviour’ = response to a stimulus, then that’s really what plants are doing too. I guess it’s just hard to think that something (usually) green, (usually) fixed in place, & with no nerves or muscles is able to behave – but plants do, & some of their behaviour is really quite subtle. You’re probably familiar with plant responses to stimuli, including tropisms, circadian rhythms, & flowering in response to changes in photoperiod. But there’s more: not only are there plants that actively hunt, but plants can also communicate – with each other, & in some cases with animals as well.

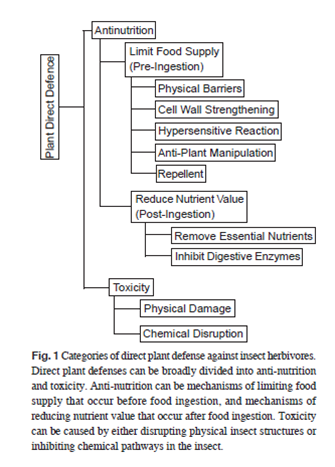

For most plants herbivores represent a major, daily threat. Plants can respond directly to herbivore attack in a number of ways. (Years & years ago – while I was a school teacher in Palmerston North – I watched a program called The 300-million-year-old war, about the arms race between plants & animals. It was excellent, but I haven’t been able to find a copy of it since…) These responses aren’t limited to the production of toxic chemicals, but can also include a range of events – shown in the figure below – that limit food supply or reduce the availability of nutrients to the animal doing the damage. (Scientists are very interested in the processes involved because an understanding of what’s going on has obvious implications for agriculture.)

(Figure from Chen, 2008)

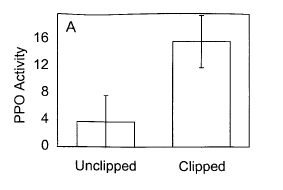

But it turns out that plants can also warn others of a herbivore’s attack – & this warning isn’t limited to members of the same species. In 2000 a series of experiments by Karban et al. demonstrated that undamaged plants respond to dues released by neighbours to induce higher levels of resistance against herbivores in nature. The researchers studied sagebrush and tomato plants, & looked first at how sagebrush responded to grazing by grasshoppers & cutworms, & also to simulated grazing (clipping the plants with scissors). They found that the plants released a volatile chemical, which they already knew could induce herbivore resistance in wild tobacco plants. The next step was to grow tobacco plants next to sagebrush plants (clipped and unclipped): tobacco growing next to clipped sagebrush produced more of a possible defensive chemical.

Fig 2: Levels of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity for tobacco plants near clipped or unclipped sagebrush neighbours. (from Karban et al. 2000)

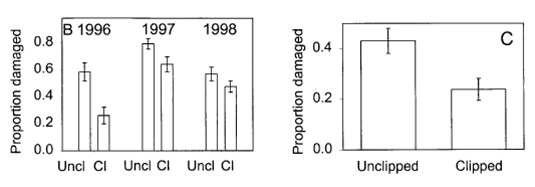

And – tellingly – tobacco plants near clipped sagebrush experienced greatly reduced levels of leaf damage by grasshoppers and cutworms… compared to unclipped controls.

Fig 3: B Maximum proportion of leaves that were damaged by grasshoppers during each of three seasons on tobacco plants near clipped (Cl) or unclipped (Uncl) sagebrush. C Maximum proportion of leaves that were damaged by cutworms during the 1966 season on tobacco plants near clipped or unclipped sagebrush. (from Karban et al. 2000)

The tobacco plants seemed to gain more than immediate protection from grazing, as the term observed that tobacco plants with clipped sagebrush neighbours produced more flowers & seeds (which could translate into increased reproductive success) over a five-year period, although there was considerable variation from year to year. You have to wonder how widespread this sort of communication is. Karban & his colleagues didn’t see any evidence that tobacco plants communicated with each other, for example. And initial work on other species that normally grow near sagebrush suggested that one such species might gain herbivore resistance, but that two others showed no response at all.

And there’s more – plants under attack by herbivores can also use volatile organic chemicals (VOCs) to signal to predators, leading them to a source of food (those hungry little herbivores): daily predation rates [on herbivores] on plants releasing VOCs… were 4.9 to 7.5 times higher than those observed on control plants (Kessler & Baldwin, 2001). Intriguingly, in at least some cases Kessler & Baldwin found that in addition to attracting predators, some VOCs also reduced the rate at which other herbivores laid eggs on the plant.

Plants – much more than you expect 🙂

M-S.Chen (2008) Inducible direct plant defense against insect herbivores: a review. Insect Science 15: 101-114. doi 10.111/j.1744-7917.2008.00190.x

R.Karban, I.T.Baldwin, K.J.Baxter, G.Laue & G.W.Felton (2000) Communication between plants: induced resistance in wild tobacco plants following clipping of neighbouring sagebrush. Oecologia 125: 66-71

A.Kessler & I.T.Baldwin (2001) Defensive function of herbivore-induced plant volatile emissions in nature. Science 291 (5511): 2141-2144.doi 10.1126/science.291.5511.2141