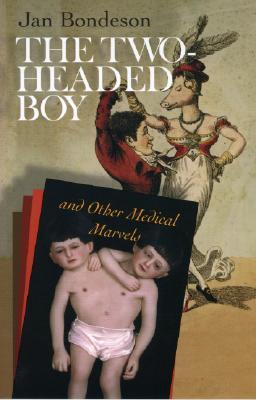

Book Review: The Two-Headed Boy and Other Medical Marvels

by Jan Bondeson

Cornell University Press, USA (2004)

Paperback: i-xxii, 297 pages

ISBN: 0-8014-8958-X

RRP: US419.95

It's all Grant's doing, really. If he hadn't picked up on an off-hand comment of mine (relating to vipers in bosoms) & turned that into a catchy blog post, I quite probably wouldn't have gone looking for other books by Jan Bondeson, or found The Two-Headed Boy and Other Medical Marvels.

This is a fascinating, saddening, and occasionally appalling book by a humane and extremely well-read author. The subjects of Bondeson's essays are those who are (or were, for these are historical essays) in someway very very different from the rest of us: the exceptionally tall, the enormously obese, the unnaturally hairy, the two-headed boys of the title. Those who in what we'd like to regard as a less-enlightened age would have spent their lives in what were then called 'freak' shows, for others to gawk and gape at. (Not that this horrified fascination with those who are different has disappeared. We just don't deem it appropriate to pay to indulge it.) And while the money may have poured in from the gawkers, all too often most of it made its ways into the pockets of 'managers', and not the afflicted individuals. (Although there were exceptions, which we'll come to shortly.)

One of the things I particularly enjoyed about the book was its interweaving of scientific and historical perspectives. Did Countess Margaret of Henneberg really have 364 – or was it 365 – children all at once? Today we'd immediately say, well of course not! But then, what are the origins of the tale described in Bondeson's essay, "The strangest miracle in the world"? The author examines the development of the legend over the years, noting with wry amusement that until quite recently childless women would wash their hands in the bowl in which the unlikely children were supposedly baptised – even though the original was destroyed long ago. And he shows how science has a part to play in the explanation: it's possible that the Countess delivered a hydatidiform mole. Although you'd think that the midwives might have had some experience of this condition, the mass of small blobby bits might have been seen by them as a large number of gravely undersized babies.

At least Countess Margaret wasn't displayed for money (although the local townsfolk must subsequently have made quite a lot out of tourists), but money's involved in most of the stories. (And attention, which may well have been the driver for the poor lady who pretended to lay eggs – a tale which also attests to the extreme gullibility of those in attendance at the delivery!) Both Daniel Lambert (for a time the fattest-known human, although more recently he has been outweighed by a man nearly double Lambert's 700+ pounds) and the 'Swedish Giant', Daniel Cajanus, parlayed their physical extremes into quite comfortable livings, for not only were they charming and intelligent men but they also had the sense to manage their own affairs. All too often that hasn't been the case, with children put on display out of desperation or greed on the part of parents or 'managers'.

Of those children, I sometimes wonder if our most awful fascincation might not rest on conjoined twins. Bondeson discusses several examples, including parasitic twins and two-headed children. Apparently dicephalus (two-headed) twins represent around 11% of conjoined twins, the great majority of whom die before or soon after birth; certainly a google search will produce more images than you may be comfortable with. I first heard of them when reading Stephen Jay Gould's essay on the twins Ritta-Christina, in which he not only discussed the children's short, sad lives but also the issue of what constitutes an individual. Bondeson also tells their story, but the two-headed boys of his title had a better time of it; in fact, he describes Giovanni and Giacomo Tocci as the "most celebrated pair of dicephalus conjoined twins of all times". While most dicephalus twins are short-lived, often due to other structural abnormalities in one twin or the other, the Tocci brothers were born in 1877 and lived at least into the second decade of the 20th century, at least in part because the boys were 'symmetrical' in that both seemed to have properly-developed hearts and lungs. Like all the dicephalus twins described in the book, the Toccis were two distinct individuals with different personalities and intellects.

And this, of course, poses some serious ethical questions. While it is possible to separate some conjoined twins, depending on the degree to which they share organs and blood vessels, to do this for dicephalus twins means that either both would spend the rest of their lives incapable of independent movement & with significant post-surgical disfigurement, or one would be sacrificed that the other might live. To whom should this decision fall? (The parents of perhaps the most famous living dicephalus twins, Abigail & Brittany Hensel, never considered this option, & their daughters are now young adults.)

Yes, this is a fascinating and thought-provoking book, not least because it offers a discomforting mirror in which to review how we see those who are so different from ourselves.

Grant says:

It’s all my fault, huh?

That looks an interesting book. I’m a bit of a fan of the issue of how others act to those that differ from them. One thing I’d add is that some disabilities or differences don’t have obvious external features, at least not to those who have no familiarity with the disability or ‘condition’. It can mean the people react in ways that others might not expect or find difficulty in doing some things, that without knowing about the cause of their difference or disability can led to perceiving the person the wrong way.

It looks like a book I’d read if I ran into a copy. The Dunedin library doesn’t have this, although it does have The great pretenders : the true stories behind famous historical mysteries (which is unfortunately held out at Mosgiel).