Like probably everyone reading this, I have always thought that spiders are carnivorous, sucking the precious bodily fluidsA from their prey. I mean, those fangs!

And I was wrong, for it seems that some spiders eat some plant material alongside their liquid meals – and some are almost fully vegetarian. A just-published paper (Painting, Nicholson, Bulbert, Norma-Rashid & LI, 2017) notes that while most of these spiders take nectar from flowers, there’s even one – with the delightful name of Bagheera kiplingiB – where much of its diet comprises the nutrient-rich leaf tips of acacia trees (more on that later).

The nectar-eating spiders don’t rely exclusively on sweet treats; the sugar they obtain supplements their main diet. Apparently the sugar-sipping habit incurs a certain amount of risk. This is because ‘extrafloral’ nectaries (eg at the bases of leaves, or on the leaves themselves) are used and guarded by ants. This behaviour itself is an interesting one, as it’s an example of a mutualistic relationship between the ants and the plants. The ants obtain nutrients, and their aggressive behaviour towards other animals can reduce damage by herbivores. Painting and her colleagues comment that other invertebrates – such as spiders – typically feed from these nectaries only when the ants are absent, but found evidence that

the jumping spider Orsima ichneumon guards extrafloral nectaries through active confrontation with ants and by depositing silk barriers to inhibit their competitors.

The researchers were intending to investigate the hypothesis that the flamboyant little spiders are ant mimics, an hypothesis which – given the bright colours of this species and the generally uniform dark colours of ants – sounds a little unusual. Their plan was derailed by a landslide that meant they couldn’t get to their field station, but that didn’t stop them making roadside observations instead.

Figure 1: a male Orsima ichneumon showing off his medley of colours. From Painting et al., 2017

The team spotted a female O.ichneumon feeding from a nectary on a leaf, a behaviour that didn’t take them totally by surprise as other scientists had already reported such behaviour in spiders. What was unexpected was the fact that she then laid down patches of silk around each nectary, after feeding there. Nor was this behaviour isolated to a single individual. And what’s more, the researchers also observed the spiders chasing smaller ants away from their feeding spots, and avoiding larger ones. As a result they formed the hypothesis that the silk deposits – made at some energy cost to the spider – act as a deterrent to the ants, although they note that this suggestion has yet to be tested, along with the idea that the silk might be a form of spider GPS, identifying the location of food sources. But why hang around on plants where there are aggressive ants to contend with, rather than go somewhere else with more insect prey & fewer ants? Painting el al. suggest that moving around between plants may increase the risk of predation, whereas staying put might afford some passive protection due to the ants guarding ‘their’ plants. Plus, the energy pay-off from nectar feeding may outweigh the costs of making the silk & chasing away the smaller ants.

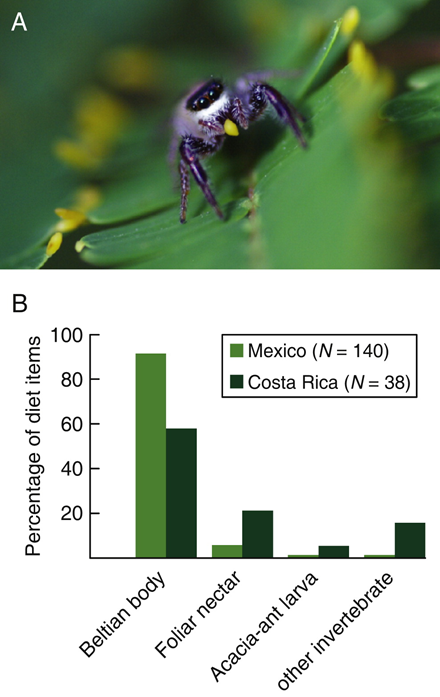

Now, on to Bagheera! I was sent a delightful link about this little jumping spider as a result of tweeting my surprise that vegetarian spiders are even a thing 🙂 B.kiplingi lives on a Central American species of Acacia that’s also defended by ants, and which produces structures called Beltian bodies for ant consumption. The spider gives adult ants a miss (although it eats their larvae – and plant nectar), but it eats a lot of the Beltian bodies: in the original paper Meehan, Olson, Reudink, Kyser & Curry (2009) note that these plant structures make up 60-91% of the spiders’ diets. This is strange, to say the least, as they turn out to be very high in fibre and low in fat.

Fig. 2 Evidence of herbivory in the jumping spider Bagheera kiplingi. (A) Adult female consumes a Beltian body harvested from the tip of an ant-acacia leaflet. (Photo: M.Milton.) (B) B. kiplingi diet estimated from field observations. Beltian bodies contributed more to the spider’s diet than did other food sources, especially in Mexico (sample sizes refer to numbers of food items observed). From Meehan, Olson, Reudink, Kyser & Curry (2009)

Meehan & his colleagues noted that the spiders live almost exclusively on acacias guarded by ants, living mostly on older leaves where ant patrols are less frequent, and avoiding ants when they’re encountered. That they can survive on a high-fibre diet suggests that their gut physiology is quite different from that of their carnivorous relatives; either that, or they’ve acquired some gut commensals that do the job for them. The fact that they’ve cut out the ‘middle man’ (the ant larvae) to consume plant material directly may allow more spiders to live on a single plant than would be the case if they were still carnivorous.

Meehan et al. conclude by noting how the spider’s unusual change in diet was dependent on the ant-Acacia relationship:

The host-specific natural history of B.kiplingi demonstrates that commodities modified for trade in a pairwise mutualism can, in turn, shape the ecology and evolutionary trajectory of other organisms that intercept these resources. Here, one species within an ancient lineage of carnivorous arthropods – the spiders – has achieved herbivory by exploiting plant goods exchanged for animal services. While the advanced sensory-cognitive functions of salticids may have preadapted B.kiplingi for harvesting Beltian bodies, this spider’s unprecedented trophic shift was contingent upon the seemingly unrelated coevolution between an ant and a plant.

A Sorry, couldn’t resist a Dr Strangelove reference 🙂

B how could you not love a cute little creature with a name like this?

CJ Meehan, EJ Olson, MW Reudink, TK Kyser & RL Curry (2009) Herbivory in a spider through exploitation of an ant-plant mutualism. Current Biology 19(19) R892-893. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.049

CJ Painting, CC Nicholson, MW Bulbert, Y Norma-Rashid, & D Li (2017) Nectary feeding and guarding behaviour by a tropical jumping spider, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 15(8). DOI: 10.1002/fee.1538