By the end of the school year, year 13 students preparing for Schol Bio should have a pretty good grasp of the concepts & content they’ve encountered in their studies. What tends to throw some, though, is the fact that the context used for each question will almost certainly be something that they haven’t come across before.

I experienced that “what the heck?” feeling myself, the first time I saw the third question in last year’s paper, which used a term I hadn’t come across before: “pivotal species”.

Why? Because I do a fair bit of reading but hadn’t actually come across that one before. (Here’s an example of the term in a different context.)

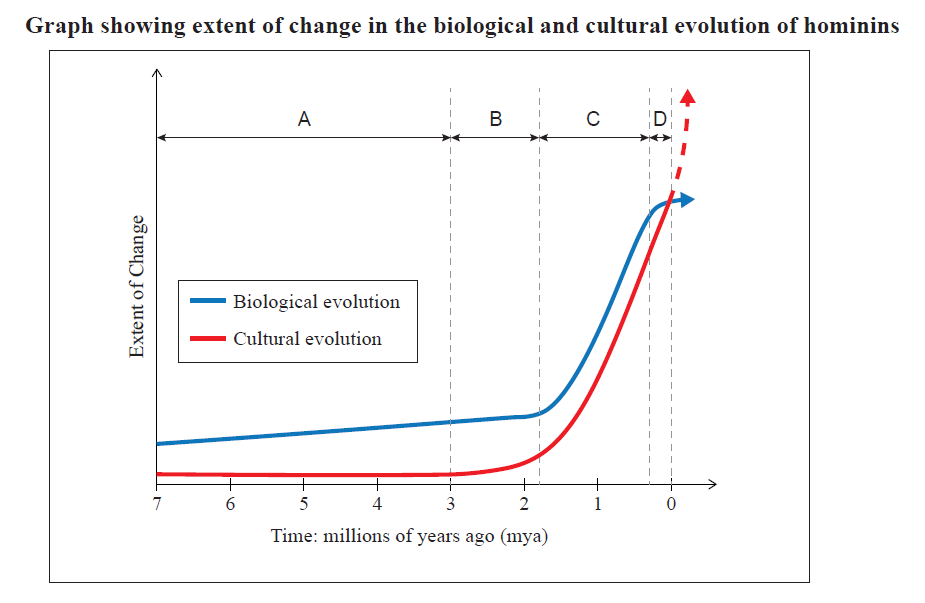

This particular question provided relatively little resource material: a graph comparing the tempo of biological and cultural evolution in hominins (divided into four time periods), plus a little material on H.erectus. So those answering it had to make good use of their own knowledge of this particular species, and others, in writing their response.

The actual question was (as usual) in two parts:

Analyse the information provided in the resource material and integrate it with your biological knowledge to:

- compare and account for the differences in the rate of change for biological and cultural evolution shown by the graph. Refer to each of the timespans indicated (A, B, C, D)** in your comparisons.

- Analyse the biological and cultural evolution of H.erectus to discuss why H.erectus could be considered a pivotal species in the evolution of modern humans.

In period A, it’s fairly clear that there’s slow incremental change in biological evolution, and no real evidence of anything in the cultural sphere. (Having said that, I’d give good odds that cultural change was happening, but that it wasn’t leaving evidence that we’d recognise as such. For example, we’ve recently found that chimpanzees modify stones as tools, leaving bits & pieces behind. But would we recognise those bits and pieces as traces of tool-making activity?) The biological changes were associated with enhanced bipedalism (eg decreased size of the nuchal crest. more central position of the foramen magnum under the skull) and other adaptations to a terrestrial lifestyle. Students could have mentioned species like Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4mya), with its mix of early adaptations to bipedalism with some evidence that it still entered the trees from time to time, Or the earlier Sahelanthropus tchadensis, which at 6-7mya shows intriguing signs of early bipedalism.

In B, between 3 and 1.8 million years ago (mya), biological evolution continues on that slow upwards trend while cultural evolution shows a bit of an up-tick. That cultural change reflects the Oldawan tool culture, associated by most of us with Homo habilis, although we now know that there are even older stone tools that predate habilis & so must have been made by another hominin species. On the biological front there’s still that slow, steady change, with changes in the hand (increased manual dexterity) and cranium (which in habilis is noticeably larger than that of the australopiths).

Then, in the period 1.8mya to ~300,000 ya (timespan C), both cultural and biological evolution accelerate sharply. This time period covers most of the ‘lifespan’ of Homo erectus, the species responsible for the Acheulean tool culture and its typical ‘hand axes’ (and more), and the development of the controlled use of fire. These new, more sophisticated technologies allowed for greater processing of food and other resources, which in turn could underlie biological changes, especially in the size of the brain. Having more access to resources would allow the development of bigger social groups, and it’s been argued (here, for example) that increasing group size is linked with increasing brain size. However, other researchers have found that diet is a better predictor of brain size in primates.

Either way, at this point in our evolutionary trajectory, there were probably feedback loops between cultural & biological evolution, with changes in one allowing (or perhaps driving) changes in the other.

And finally, period D (300,000ya to the present) sees a continued rise in cultural evolution, while biological evolution slows. This is the timespan of our own species, Homo sapiens. In cultural terms, Mousterian tools appear around 300,000 ya – another technological advance that would again have increased the range and amount of available resources, including food. More recently there’s evidence of abstract thought (& presumably complex language); that, plus increasingly sophisticated technology, gave our own species greater control of the environment, and at that point the rate of biological change began to taper off (though of course, it’s still happening at the genetic level).

So, why might we say that the evolution of erectus was a pivotal event? Essentially, because of the significant changes and events that are associated with that species. Homo erectus had a brain size substantially greater than that of earlier hominins. It was taller than its predecessors, and was the first hominin to migrate out of Africa. In addition, there are the development of the Acheulean toolkit, mastery of fire, and the appearance of a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Endocasts provide evidence that this larger brain (on average, it was around 50% bigger than that of habilis, and ~ 70% the size of ours) included regions known as Broca’s & Wernicke’s areas (although they were smaller than in our own brains). In sapiens these are associated with the ability to organise and interpret vocalisations – something that would support social cooperation, including hunting. And that cooperative hunting would have had an impact on diet.

The species’ longer legs and arched feet meant that erectus had very efficient bipedal locomotion – important both in moving through their immediate range, and in that movement out into Europe and Eurasia (which would have opened up new territory and resources for exploitation). The more sophisticated Acheulean tools enabled changes in how those resources were processed, compared to the earlier Oldowan culture,

And then fire. Fire provided a range of benefits. Heat & light are the most obvious: heat would open up colder environments for occupation, while light would extend the amount of time available for various tasks and activities. But in addition, cooking changes food. It softens it and can make nutrients more accessible; it kills parasites; and processing food can also detoxify some poisons. These things have a big positive impact on diet (& potentially on brain size & complexity – but see the comments above).

Thus we could view H.erectus as a pivotal species, with its cultural and biological adaptations providing the impetus for the evolution in turn of our own species.

** Remember – in answering a question like this you should start with A & work through in sequence to D!