So, yesterday we had our Science Communication students looking at social media and blogging in particular. Alison Campbell and I talked through what makes a good science blog, and the students got to explore sciblogs.co.nz and look for themselves*. In the coming week, the students need to put up a blog entry themselves. (I’m afraid these will be private to the paper, though we might persuade the authors to release the best of them more widely.)

As we talked with the students about blogging, a repeated question was “how do I choose a topic?” I think the same advice applies to blogging as it does to writing in general: “Write about what you know.” So, I ask the students what they are majoring in. What topics in their studies have really got them saying “Ooo, that’s interesting”? What do they do in their spare time? What have are they interested in?

So, for my next post (which I really should do now, given that I’m asking my students to do one), I shall follow my own advice, and blog about cricket. Well, kind of, anyway.

In the last week, I have followed intently two really great Test Matches – Sri Lanka versus England in Kandy, and Pakistan versus New Zealand in Abu Dhabi. Both matches were see-saw contests, being unclear right to the end who was going to come out on top. Although the Sri Lankan second innings finally gave way comfortably short of their target, New Zealand had to rely on an oh-so-typical Pakistani batting collapse to get past their opponents by the narrowest of margins. Both matches were played on awkward batting surfaces (the Pakistan – New Zealand match in particular) which gave the bowlers the upper hand for much of the match and limited the runs scored.

What makes the surface so awkward for batting? A lot of it is down to inconsistency in the bounce of the ball. If one ball jumps off a good length to hit you on the glove, while the next, almost identical ball scoots along the ground and hits your feet, batting is going to be a bit of a mission. Similarly, if one ball will bounce and go straight on, while the next will spin significantly, with no apparent clue as to which will happen, your innings may be shorter than you wish for. Of course, a good spin bowler will exploit that. Much of the inconsistency comes down to the quality of the pitch – a beautifully snooker-table-flat pitch which doesn’t crack and distort as the match goes on is going to give a lot more consistency than a bumpy surface, and therefore we can expect batting to be much easier and more runs to be scored.

When I played socially in the UK, our ‘home’ ground generally was prepared well. Not that I was good enough to really cash-in on it. But the same couldn’t be said of the surfaces in the batting nets, which were truly evil. When Tom our fast bowler got bowling at you in the nets (particularly if he was in a bad mood), the most likely outcome would be a plethora of bruises as the bounce was so unpredictable. I’m not sure practice in the nets did my batting any good whatsoever.

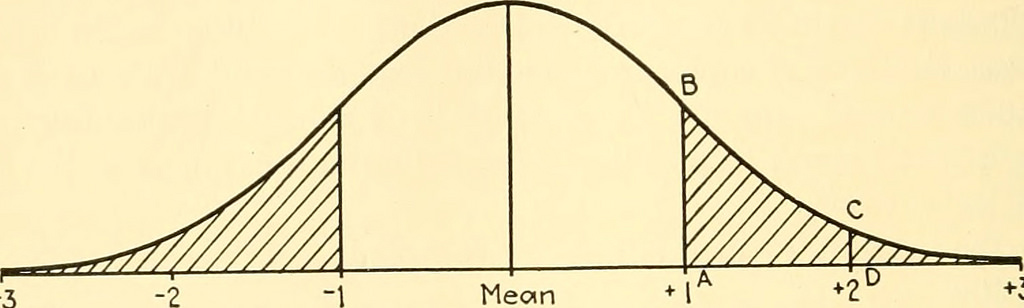

So, what has any of this got to do with science? Variability is a big deal in science experiments. In physics, normally things are pretty repeatable. If I do two nominally identical experiments on different days, I would expect to get very similar results. But in biology, variations can be much larger. Different people, for example, can respond very differently to the same dose of a drug, for example. Or the size of a muscle twitch caused by magnetic stimulation of the brain might be much larger in one than another. A PhD student of mine has seen this in recent days with some of her results – she’s been applying magnetic stimulation to biological tissue and measuring how various properties change. In some cases, she’s seen a big increase in the output measures – the size of the response increased by 20%, but in some cases the same stimulus gave an equivalent reduction in the response. Overall, alas, after analyzing lots of samples, we see no overall effect. But because of the large variability, we do need lots of samples before we can conclude that.

In physics, while dealing with uncertainties in measurement is absolutely necessary, it’s probably rare to get that kind of variability from one measurement to another. I think that is why biologists tend to get taught more statistics than physicists.

Perhaps physicists should play more cricket, instead.

*Scibloggers, you might like to know that some of your posts were graded by the students, in terms of relevance, clarity of writing, adding value to the topic, use of external links and resources and attribution of sources.