Quote by Jeanette Winterson

Blog by Angela Fuimaono, Summer Scholar 2022

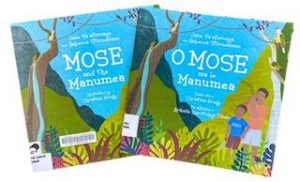

Picturebooks are truly doors, windows and mirrors to different worlds (Bishop, 1990). For many children who are Pasifika there are not many books which depict their own world, and even less written in their own languages. With over 13 percent of New Zealand children being of Pacific descent it is hard to understand how so little resources are available for them. Last year’s University of Waikato Summer Scholar, Cushla Foe, was only able to find 91 Pacific Picturebooks available for students written in the last ten years (Kelly-Ware, Foe, & Daly, 2021). As a mother of four Samoan children I found it hard to find books to read to my own children when they were younger. They were not in libraries or bookstores. And the ones I did find were very hard to read and didn’t engage my children’s imagination. Being able to be involved with research that was looking at how teachers and children respond to Pacific Picturebooks was something that felt so right and so needed.

The pilot study took place at a kindergarten staffed by Pasifika teachers and catering for Pasifika children and their families. It was an eye opening experience which made me question many different aspects of the research process. How we engaged with teachers and children needed to be relational and done with the intention of creating va (space) for all those involved to share their cultural capital. Together, as researchers and the teachers involved, we met together to have a talanoa with a focus on relationship building which strengthened and enriched the observations and data collected. This knowledge sharing was instrumental in how we chose to structure the research. Sharing stories about the children, ourselves and the research was a natural way to convey complex ideas in keeping with the purpose of talanoa (to share stories, build empathy and to make wise decisions for the collective good). When teachers and children interact in a kindergarten which values deeper connections, a simple analysis of those interactions does not do the relationships justice.

One story we delved further into was during a quiet day at the kindergarten. The children were able to make connections to the imagery in the Pacific Picturebook being read by their teacher. Because of the deep relationships that existed between children and teachers, this amazing teacher was able to extend the children’s knowledge and learning by putting the book down and engaging them in play related to the picturebook. She worked together with the children to construct their own traditional fale (house) from recycled resources found around the kindergarten. Many teachers would have continued to read without giving children the space to pursue their own learning, so it was an amazing experience to see the children supported by their teacher to learn new skills extending from their own previous cultural knowledge. She herself said it was a “wow moment” for her. This experience and others showcase the way that emergent curriculum can benefit and supplement children’s learning. These children were able to walk through the doors of the book and after they had made their house the teacher finished reading the book in the new fale connecting back to the journey they had taken through the pages of the story.

In Te Whāriki, the Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood curriculum there are different strands and principles which weave together to create an environment that fosters success for all students. There is a focus on culture, language and identity (Ministry of Education, 2017). When children can see their language and culture depicted on the vibrant pages of a picturebook it strengthens their identity as strong Pacific Island children who have a wealth of cultural capital to draw on as they progress through their school journey -a journey that can be fraught with peril, as they navigate a system that is dominated by European discourses and forms of knowledge. Our research did not just look at how children responded to Pacific picturebooks, but also how the teachers responded. I’ve learnt that the way teachers’ value books from different cultures can affect children’s own feelings of self-worth.

Many interesting findings have come from this short pilot research study. One finding that I found intriguing was how not all Pacific picturebooks are made equal. There are some books which are simple translations from English, where the imagery and content do not mirror the authentic culture it is meant to represent. Yet, other books are beautiful portals to a world you can recognise and appreciate through the stunning illustrations and the style of writing, which effortlessly include culturally specific words. Also the content is true to the beliefs and values of the peoples as a whole. Reading these books can transport you back to an island you love with a flip of the page. These are the books which our children need to be able to connect to, rather than negative or whitewashed stereotypes portrayed in far too many of the Pacific books available.

Picturebooks are a well-established part of many western societies. However, for Pacific Island nations much of their knowledge is transmitted through song, dance and oral performances. For many children at the kindergarten it was hard to learn the social norms surrounding the use and care of books. Yet they readily sang songs in many different languages, along with sometimes complex hand movements. They easily expressed cultural values of love, respect, inclusion, belonging, service and spirituality. These values, all seen as factors of success, are expressed in Tapasā: Cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners (MoE, 2018). Judging by the Tapasā Pasifika Success Compass (p. 4) these young children are well on their way to being successful Pasifika adults. Though if they attend a primarily European school, which is inevitable, they face the real possibility that those attributes will be given less value than having the ability to read, write and talk in a language different from their own. How wonderful it would be to see a system of teachers and students who worked together to provide space for all ways of being – for more doors to be opened into the rich and unique worlds of the Pacific Islands, which teachers are willing to step through and embrace other understandings of the world.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows and glass sliding doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix–xi.

Kelly-Ware, J., Foe, C., & Daly, N. (2021). Exploring Pacific picturebooks: A summer scholar’s perspective. Literacy Forum NZ, 36(3), 29–39.

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum.

Ministry of Education. (2018). Tapasā: Cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners.

About the author

Angela Matemate Fuimaono has recently completed a Bachelor of Social Sciences degree at The University of Waikato and is currently studying towards a Master’s degree in Education and Developmental Psychology at Massey University. She was the recipient of a 2021/2022 Summer Scholarship from The University of Waikato in the Division of Education.

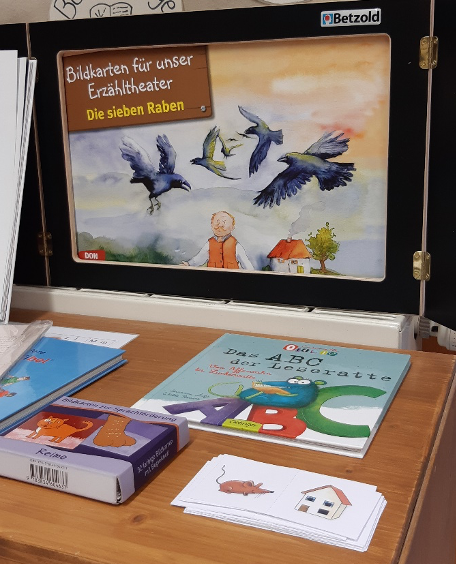

Wim pictured with a mobile kamishibai – a story theatre cabinet for showing paper dramas

Wim pictured with a mobile kamishibai – a story theatre cabinet for showing paper dramas The website describes Kamishibai as part of an age-old visual narrative tradition that originated in Buddhist temples in Japan during the 12th century. Monks used image roles to pass on moralizing stories to a predominantly illiterate audience. The kamishibai storytelling technique continued for centuries and had an unprecedented success between the two world wars. For thirty years, from 1920 to 1950, this narrative technique caused a furore in Japan as Kamishibai storytellers rode around on bicycles which had the small wooden theatre mounted on them (like in the image above). They installed themselves on street corners or in parks and at that time more than five million children and adults enjoyed the Kamishibai almost daily. With the rise of television, the mobile storytellers slowly disappeared from the streets. Apparently this unique story theatre has been making a worldwide comeback for several years

The website describes Kamishibai as part of an age-old visual narrative tradition that originated in Buddhist temples in Japan during the 12th century. Monks used image roles to pass on moralizing stories to a predominantly illiterate audience. The kamishibai storytelling technique continued for centuries and had an unprecedented success between the two world wars. For thirty years, from 1920 to 1950, this narrative technique caused a furore in Japan as Kamishibai storytellers rode around on bicycles which had the small wooden theatre mounted on them (like in the image above). They installed themselves on street corners or in parks and at that time more than five million children and adults enjoyed the Kamishibai almost daily. With the rise of television, the mobile storytellers slowly disappeared from the streets. Apparently this unique story theatre has been making a worldwide comeback for several years

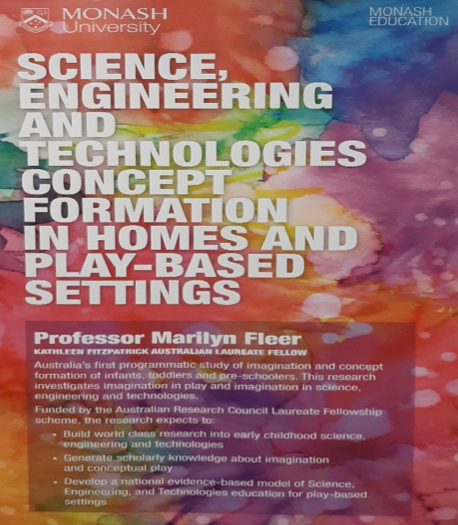

A Conceptual PlayWorld is an imaginary scenario created by an educator where young children are invited to go on imaginary journeys, meet and solve challenges, and learn STEM concepts – all while playing. A Conceptual PlayWorld can be inspired by a children’s book or a fairy tale story, and it can be setup in an average classroom. Imagination is the limit!

A Conceptual PlayWorld is an imaginary scenario created by an educator where young children are invited to go on imaginary journeys, meet and solve challenges, and learn STEM concepts – all while playing. A Conceptual PlayWorld can be inspired by a children’s book or a fairy tale story, and it can be setup in an average classroom. Imagination is the limit! Teachers are encouraged to start with a simple story such as Rosie’s walk (Hutchins, 1967), incorporate drama and learn about something like ‘prepositional language’ (on, over, under, behind, in front, etc.) and of course PLAY these concepts with children in your imaginary Rosie’s farm.

Teachers are encouraged to start with a simple story such as Rosie’s walk (Hutchins, 1967), incorporate drama and learn about something like ‘prepositional language’ (on, over, under, behind, in front, etc.) and of course PLAY these concepts with children in your imaginary Rosie’s farm.