April/ May 2020

Recently I spied a link to the Education Hub where I found a series of three picturebooks about a bear who goes into lockdown. The books contain great text and photographs depicting daily life from the diary of a bear. Given the currency of this situation and the bears in my window looking out onto the street I decided to investigate. I tracked down the author and emailed Professor Carol Mutch from the University of Auckland about her latest ‘output’. Carol replied, “I didn’t expect them to take off the way that they have but I’m delighted that people are finding them useful and fun. There will be one more book but then Bear will go into hibernation as winter is coming — and I need to get my life back :-).”

On the back cover of the first book, Carol wrote, “On March 25, 2020, New Zealand went into lockdown. This was the final step of a four-stage approach to fighting the COVID-19 virus. Bear’s story was originally written to entertain family and friends and each day a new episode appeared on the author’s Facebook page. The story gained wider attention as it is not just a story about a toy bear. It contains many aspects of life under lockdown that readers will resonate with. It can also provide parents and teachers with an opportunity to discuss Bear’s adventures with children and relate them to their own experiences.”

The first book is called Bear goes into lockdown. We meet Bear and follow his first week in lockdown as he begins to make sense of how his world and the world of his humans has changed. The second book is called Bear settles into lockdown. Bear finds that lockdown is not always easy but you can change your attitude and try to make the best of it. Having Easter weekend to look forward to provided a bright spot in Bear’s lockdown.

The third (and meant to be final) book in the series is called Bear stays in lockdown. Bear faces more highs and lows. He joins in as many household activities as he can but he misses his friends. To his delight, his best friend Alligator comes out of quarantine and makes a surprise visit. After some fun with Alligator, Bear learns that it is important to stay true to who you are.

Another email from Carol arrived just as this blog was going to press. She wrote, “I have had as much feedback from adults as children. They have told me that getting up each morning to see Bear’s adventures on Facebook was often the highlight of their day. One woman said, “I have to keep reminding myself that Bear is not real. I have had many people ask when they are coming out in hard copy — I guess that’s my next challenge to find a publisher”.

And surprise, surprise she sent another book in pdf form and the link is now available. The fourth book is called Bear ends his lockdown. Bear ends his lockdown, Bear and Alligator make their own fun, which doesn’t always go well. When it is announced that Level 4 lockdown will end after Anzac weekend, Bear has some hard choices to make. Should he stay and enjoy a little more freedom or is it time for him to go back to the toybox?

Picturebooks such as the Bear in lockdown series can act as both mirrors and windows on the world. As mirrors they can reflect children’s own lives (familiar objects and content), and as windows they can give children a chance to learn about someone else’s life (unfamiliar objects and content). These ideas are eloquently described by Bishop (1990) who states,

Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror (p.ix)

Professor Carol Mutch’s delightful books are a fine example of the power of picturebooks and they exemplify this famous quote. Her photograph illustrations like those in many picturebooks can be children’s first visual introduction to an outside world full of people, places and things that are different from or similar to their own (Kelly-Ware & Daly, 2019).

The Bear in lockdown series mirrors what is happening in our lives at the moment with us having been in lockdown for the past six weeks. They are also windows and show us a bear living among humans with his friends – sometimes in the window or on the letterbox or up a tree near the footpath like I saw on my neighbourhood walk yesterday. I look forward to reading these and other books with my great grandchildren when this rahui (lockdown) is over.

Carol gave us permission to put links to these books up on our site, advising that they are not exclusive to any one outlet. Blog readers may also be interested in a digital book about Coronavirus illustrated by Gruffalo illustrator Axel Scheffler released in early April 2020. This information book is aimed at primary school age children, and is free for anyone to read on screen or print out, about the coronavirus and the measures taken to control it. Here is another list of 19 free ebooks about coronavirus.

References

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6(3), ix-xi.

Kelly-Ware, J., & Daly, N. (2019). Using picturebook illustrations to help young children understand diversity. International Art in Early Childhood Research Journal 2019 Research Journal Number 1, Article 1. https://artinearlychildhood.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ARTEC_2019_Research_Journal_1_Article_1_KellyWare_Daly.pdf

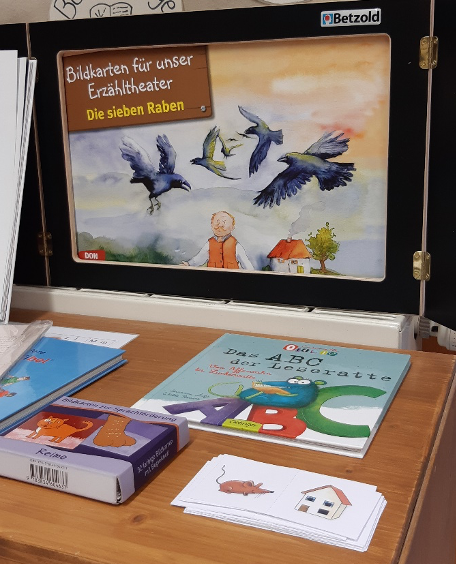

Wim pictured with a mobile kamishibai – a story theatre cabinet for showing paper dramas

Wim pictured with a mobile kamishibai – a story theatre cabinet for showing paper dramas The website describes Kamishibai as part of an age-old visual narrative tradition that originated in Buddhist temples in Japan during the 12th century. Monks used image roles to pass on moralizing stories to a predominantly illiterate audience. The kamishibai storytelling technique continued for centuries and had an unprecedented success between the two world wars. For thirty years, from 1920 to 1950, this narrative technique caused a furore in Japan as Kamishibai storytellers rode around on bicycles which had the small wooden theatre mounted on them (like in the image above). They installed themselves on street corners or in parks and at that time more than five million children and adults enjoyed the Kamishibai almost daily. With the rise of television, the mobile storytellers slowly disappeared from the streets. Apparently this unique story theatre has been making a worldwide comeback for several years

The website describes Kamishibai as part of an age-old visual narrative tradition that originated in Buddhist temples in Japan during the 12th century. Monks used image roles to pass on moralizing stories to a predominantly illiterate audience. The kamishibai storytelling technique continued for centuries and had an unprecedented success between the two world wars. For thirty years, from 1920 to 1950, this narrative technique caused a furore in Japan as Kamishibai storytellers rode around on bicycles which had the small wooden theatre mounted on them (like in the image above). They installed themselves on street corners or in parks and at that time more than five million children and adults enjoyed the Kamishibai almost daily. With the rise of television, the mobile storytellers slowly disappeared from the streets. Apparently this unique story theatre has been making a worldwide comeback for several years

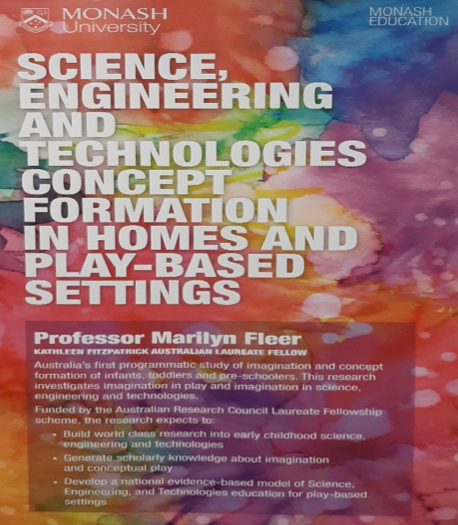

A Conceptual PlayWorld is an imaginary scenario created by an educator where young children are invited to go on imaginary journeys, meet and solve challenges, and learn STEM concepts – all while playing. A Conceptual PlayWorld can be inspired by a children’s book or a fairy tale story, and it can be setup in an average classroom. Imagination is the limit!

A Conceptual PlayWorld is an imaginary scenario created by an educator where young children are invited to go on imaginary journeys, meet and solve challenges, and learn STEM concepts – all while playing. A Conceptual PlayWorld can be inspired by a children’s book or a fairy tale story, and it can be setup in an average classroom. Imagination is the limit! Teachers are encouraged to start with a simple story such as Rosie’s walk (Hutchins, 1967), incorporate drama and learn about something like ‘prepositional language’ (on, over, under, behind, in front, etc.) and of course PLAY these concepts with children in your imaginary Rosie’s farm.

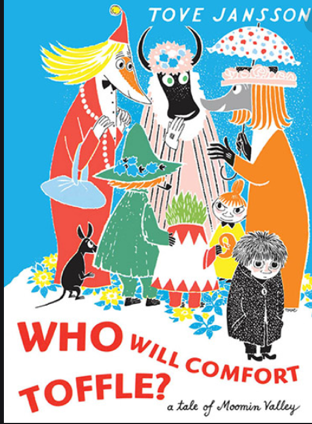

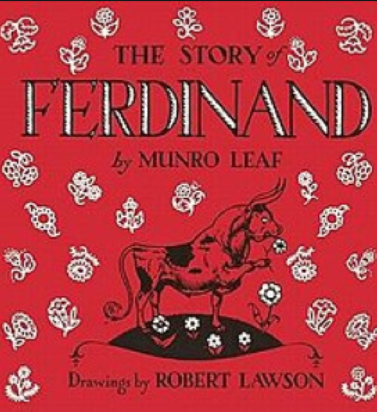

Teachers are encouraged to start with a simple story such as Rosie’s walk (Hutchins, 1967), incorporate drama and learn about something like ‘prepositional language’ (on, over, under, behind, in front, etc.) and of course PLAY these concepts with children in your imaginary Rosie’s farm. Highlights from the rest of the sessions I attended include talks about silence in Moomin stories by Tove Jansson; sessions about the silences associated with refugee voices in the picturebooks telling refugee stories, silences in the translation of picturebooks, an analysis of the silences in world tours made by Munro Leaf, author of The Story of Ferdinand

Highlights from the rest of the sessions I attended include talks about silence in Moomin stories by Tove Jansson; sessions about the silences associated with refugee voices in the picturebooks telling refugee stories, silences in the translation of picturebooks, an analysis of the silences in world tours made by Munro Leaf, author of The Story of Ferdinand

I was also able to have a tour of Astrid Lindgren’s apartment (the creator of Pippi Longstocking), still furnished exactly as it was when she died; and we were given a city reception at the Town Hall of Stockholm, in the beautiful golden hall where the Nobel Awards are given each year. So it has been a full and privileged experience which will benefit both my teaching and research into the future. I have taken the opportunity to download biographies of

I was also able to have a tour of Astrid Lindgren’s apartment (the creator of Pippi Longstocking), still furnished exactly as it was when she died; and we were given a city reception at the Town Hall of Stockholm, in the beautiful golden hall where the Nobel Awards are given each year. So it has been a full and privileged experience which will benefit both my teaching and research into the future. I have taken the opportunity to download biographies of

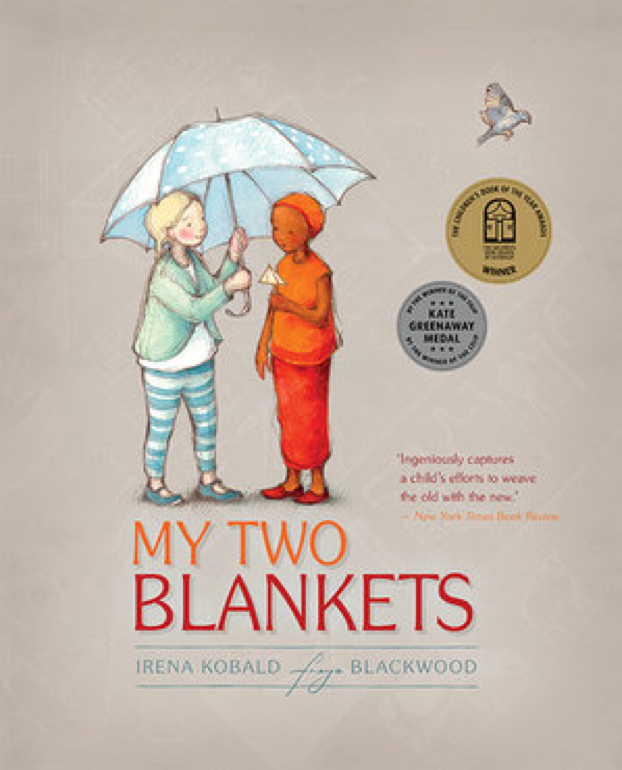

Since then I have been looking for picturebooks that may act as mirrors and windows on the world to use with young children in the context of diversity and social justice, and to help children cope with tragedy. The following website is worth investigating.

Since then I have been looking for picturebooks that may act as mirrors and windows on the world to use with young children in the context of diversity and social justice, and to help children cope with tragedy. The following website is worth investigating.